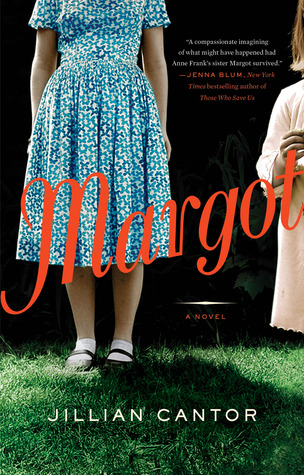

Book Club: ‘Margot’

Our Book Club meets again on Sunday, March 30 at 10:00 am, to discuss Margot, by Jillian Cantor. This novel imagines what would have happened if Anne Frank’s sister Margot had survived the war and immigrated to the U.S.

Our Book Club meets again on Sunday, March 30 at 10:00 am, to discuss Margot, by Jillian Cantor. This novel imagines what would have happened if Anne Frank’s sister Margot had survived the war and immigrated to the U.S.

Oprah recommended this book back in September, here’s a review by Abbe Wright: In the spring of 1959, quiet Margie Franklin is a secretary at a law firm. But this unassuming woman harbors a secret that could threaten her newly established life: Her true identity is Margot Frank. In Margot, Jillian Cantor reimagines the life of Anne Frank’s older sister, who, along with Anne and six others, lived in an attic for two years, hiding from the Nazis. Margot also kept a diary (though it was never found), and it is from that real-life thread that Cantor derives the inspiration for her story. In this inventive narrative, after narrowly escaping death, Margot migrates to the City of Brotherly Love, where she changes her name out of fear of being outed as a Jew. She hides within her new persona the way she once concealed herself in the annex, whispering prayers on the Sabbath and always wearing a long-sleeved sweater “so the dark ink on my forearm remains hidden, unseen.” Cantor’s “what if” story combines historical fiction with mounting suspense and romance, but above all, it is an ode to the adoration and competition between sisters who were once so close that Margie feels “something is missing from me, something that feels like the phantom weight of a stolen limb or internal organ….” Despite her survivor guilt, she knows she must seize her second chance and live a life worthy of those who never got one.

Time magazine has published an exclusive excerpt from the book:

In 1944, Mother, my sister, and I waited in line after we were unloaded from the cargo train by thick black-booted men. They had pulled our arms, throwing us off the train as if we really were cargo, laughing, joking with one another in German as they did it, cigarettes hanging loosely from their mouths, thick rings of smoke swirling above their heads. We’d just been transported from Westerbork camp in Holland to Auschwitz in German-occupied Poland. It was the beginning of September, a month after we’d been ripped from the annex. The sun was shining. To walk in it, it actually still hurt my skin, as if its rays were overexposing me, after so much time hidden away.

We stood in line, and I held on tightly to my sister with one hand, my mother, with the other. Mrs. van Pels was somewhere behind us.

“We’ll be killed,” my sister whispered to me as we waited there for what felt like forever, the soles of our feet beginning to burn from standing still. It was warm outside, and we were sweating, thirsty. Even my sister’s whisper sounded hoarse.

“Shhh,” I told her. “No, we will not.” I felt I was lying to her then, but it seemed a necessary lie. I was terrified she would hear the pounding of my own heart in my chest. “Just do what they tell you,” I whispered slowly. “Don’t struggle.”

The woman in front of us in line was an older lady, older than Mother by twenty years at least, and her back was already hunched; her arms fell frail around her sides. The guards yelled at us in German to undress, and when she was naked, her flesh hung off her bones, loose, wrinkly. It seemed she was too old to be so naked.

Then the guards came to shave us, and she began shouting. “Jestes diablem. Jestes diablem.” She shouted it, over and over again. So loud, her voice hurt my ears.

“You are the devil,” Mother whispered, translating. “It’s Polish.” Mother knew a little Polish from a childhood friend.

My sister’s almond eyes opened wide, the way they often did. “She’s so brave,” she whispered.

“Don’t even think it,” I whispered to her, because it seemed they must have had a way of knowing then, even our thoughts. When you are stripped naked, shaved bare, nothing is yours anymore, nothing is left.

We stood in line again for a long time, and her words, they began to hurt my ears. My bare flesh turned numb. My ears felt like they were bleeding. Jestes diablem. The Polish woman screamed and she screamed.

The guard held her down as he tattooed her arm, and then he shoved her roughly and yelled at her in German to shut up. She was still screaming.

Finally another guard came and pulled her away into the other line, made up of people, I would later learn, who were immediately gassed, instead of put to work. They were not supposed to tattoo you if you were to be gassed right away, but with her, they made an exception.

My sister was standing just in front of me watching all of this. I saw her open her mouth, and I covered it with my hand and pushed her back behind me so I could be tattooed before her. I wanted her to see that it wouldn’t be so bad.

“It’s only a little ink, just a number. Don’t scream,” I whispered to her. “Don’t struggle. Just be quiet and do what they ask.”

Her almond eyes stared back at me, so wide they could burst. She opened her mouth again but no sound came out.

I held out my arm, closed my eyes. My skin singed and cried out in pain, but I did not say a word. I bit my lip.

I opened my eyes again, and there it was, thick dark ink on my forearm: The letter A, followed by five seemingly random numbers.

My sister went just after me, and her number was one digit higher than mine.

“It doesn’t mean anything,” Mother said afterward. “It is nothing. It cannot mean something. We cannot make nothing mean something, girls.”

“When we go home, it’ll be a badge of honor,” my sister said.

* * * * *

“Margie.” Shelby interrupts my thoughts. “Are you okay? You look like you’ve seen a ghost.”

“Yes,” I whisper. So many ghosts. Everywhere, all the time. I am one myself, am I not?

“Your face is so flushed,” Shelby says. “It’s warm in here. Take your sweater off. It’s 1959, for goodness’ sakes. A girl can show a little skin.” She laughs and holds out her own bare pale freckled arms, which radiate from her blue cotton short- sleeved dress.

But I shake my head. I will not take my sweater off. I will never take it off.